Project XP-38N

A site dedicated to the memory of those who designed, built, flew, and maintained the Lockheed P-38 Lightning in defense of freedom.

The Lockheed P-38 and its variants

by David C. Copley, last updated Mar 9, 2011

[My attempt to summarize importnt and interesting facts about the P-38, culled from a large number of sources.]

Overview

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was one of the most prominent fighters throughout WWII in both major theaters of operation. P-38s scored some of the first victories in the Pacific Theater as they served in the arctic cold of Aleutian Islands. In Europe, they often provided high-altitude long range escorts for bombers. The P-38 was originally developed in response to the US Army Air Corps' need for a high altitude 'interceptor' in the late 1930s. The Air Corps' requirements specified a craft that could reach an altitude of 20,000 ft in six minutes, attain a top speed of 360 mph and fly at full throttle for one hour. In addition, it would carry more armament than any previous fighter.

Lockheed's legendary aeronautical engineer, Kelly Johnson, drew on his past experience with twin-tail craft such as the Electra and proposed a twin-engine, twin-boom arrangement with turbo-supercharged engines. (Kelly Johnson went on to design the F-104, the U-2 and the SR-71.) The XP-38 was first flown in January 1939. After logging just a few flight-test hours, it embarked on a record-breaking cross-country flight that proved the capabilities of the design, but also resulted in its demise when it plowed into a golf course just before landing.

The only fighter-craft to remain in production throughout the war, the P-38 proved to be a very versatile platform for a wide range of operations including long-range escort, photo reconnaissance, fighter/interceptor, ground attack, and even formation bombing. It evolved through several variations, each iteration more successful than the last. Perhaps its strongest asset was its concentrated fire power. Being a twin engine aircraft allowed it to have four guns and one cannon mounted in the nose. This clustered arrangement meant that the guns did not have to be sighted to converge at some optimum target range. In the hands of a skilled pilot, the Lightning was a formidable fighter. No wonder America's top two fighter aces scored their victories in P-38s.

However, it was not without its faults. Early into the European war it gained a reputation for poor high altitude performance. Even though this was eventually traced to the use of lower-grade British fuels, the reputation remained. The two liquid-cooled Allison engines required a lot of attention, and there was trouble with the turbo superchargers as well.

The P-38 was the one of the first aircraft to seriously encounter a potentially fatal phenomenon: compressibility. During a high-speed dive the wings would lose lift, resulting in loss of control. The enemy soon began exploiting this weakness to elude the P-38s. The problem was finally solved when, late in the J series production, dive recovery flaps were added which gave pilots the freedom to enter into high speed dives with confidence. Early Lightnings also had poor roll rate and required a lot of muscle to turn. When the dive recovery flaps were added during the J-25 production block, hydraulically boosted ailerons were also added. This welcome addition gave pilots "power steering," greatly increasing the roll rate.

As the need for night fighters increased, Lockheed produced the two-seater M series. The addition of a radar operator relieved the pilot from radar duties and allowed him to concentrate on the mission objectives. Nearly 10,000 P-38s were built, the bulk of which where J and L series. After the end of the war, the Army Air Force surplused them for $1,200 a piece. Of course you had to arrange for delivery, which was no trivial task since as many of them were in the south Pacific. Today, only a handful remain. Only a few are in flying condition.

Brief descriptions of most of the major variants:

XP-38

As mentioned above, the XP-38 was Lockheed's entry into the US Army's competition for a new generation pursuit plane. Lockheed had never developed a fighter aircraft before, but the fledgling company had great confidence it could deliver. After proposing the radical concept of a twin-engine, twin boom fighter and being awarded $163,000 to build a prototype, Lockheed then invested $761,000 to develop and build the XP-38 -- a tremendous gamble on the part of the relatively new company, especially since there was never any expectation that the Army would need more than perhaps 50-100 planes total. (At that time, a Packard coupe cost about $900, and a new 2-bedroom home in California cost about $3,000. Thus, one can see that Lockheed was betting its future on the success of this plane.)

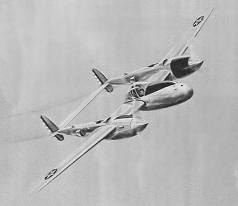

Left:

Artist conception of the XP-38 in flight. No photographs

were ever taken of the XP-38 in flight. Right: XP-38 being refuled

at Dayton, Ohio on its final fateful flight.

Left:

Artist conception of the XP-38 in flight. No photographs

were ever taken of the XP-38 in flight. Right: XP-38 being refuled

at Dayton, Ohio on its final fateful flight.

Well ahead of its time, the XP-38 was among the first to include features now common in modern aircraft, such as Fowler flaps, butt-jointed flush-riveted skin, metal control surfaces, tricycle landing gear, and a bubble canopy. The prototype was almost entirely hand-made and its aluminum skin was highly-polished.

The XP-38 rolled out December 31, 1938 under intense security. After many taxi tests throughout the month of January, it made its first flight January 27, 1939. The first flight was troublesome and nearly ended in disaster. Almost immediately upon take-off, the flaps broke and caused dangerously severe vibrations. Lt. Ben Kelsey, a highly skilled pilot who had been with the P-38 program from its inception, brought the plane under control and returned to the airstrip. After some repairs it took the skies again the next day, and the Army soon realized they had the fastest fighter plane in the world in their hands, capable of sustained speeds of over 400 mph.

Despite troubles with weak brakes and temperamental flaps, Kelsey felt the plane was ready to fly to its intended base at Dayton, Ohio for flight testing. Considering the trip from California to Ohio was practically cross-country, Kelsey and his superiors felt that if they took the plane a bit farther, they could break the cross-country speed record of Howard Hughes. By doing so, they felt they could generate great support for the new fighter. (This was an era of highly publicized aviation records, speed being one of the most sought-after. ) It was decided that he would make the attempt so far has Dayton, Ohio where he was based and if all was well with the plane, he would be allowed to continue to east coast. After all it would only be a short extra flight.

On the morning of February 11, 1939, Lt. Kelsey took off from March Field near Riverside California and made a fuel stop at Armarillo, TX before reaching Dayton. At Dayton, it was decided that while he couldn't beat Hughes' total elapsed time (due to the time taken for refueling stops) he could easily break the flight time (total elapsed time in the air). The plane was looked over and Lt. Kelsey was given the go ahead to finish the cross-country dash.

On approach to Mitchell Field on Long Island, NY, Kelsey throttled back the engines and began his descent. It appears no one had informed Mitchell Field of this very special arrival (after all the XP-38 was a secret military plane), so when he called in for landing clearance, he was put into 4th position behind some rather slow moving planes. Kelsey didn't protest the landing position, because he knew he needed some extra distance to set up his approach anyway: with XP-38's poor brakes and unreliable flaps, he wanted to land with care and utilize the most runway possible. While on the very long base leg, ice formed in and around crucial engine systems so much so that when he came into final and attempted to increase power, the engines did not respond. Kelsey couldn't quite make the runway and ended plowing into a golf course. Fortunately, he walked away unhurt, but the one-of-a-kind XP-38 was damaged beyond repair.

In total, the XP-38 had just under 12 hours of flight time when it crashed, with the majority from the cross-country flight. It had only taken off nine times and successfully landed eight times. However, it had proved its point: it was fast! And it was a good design. Not long after the crash, the Army ordered 13 service test YP-38s, and the rest is history. Because of the XP-38's relatively short service life, not much is know about its actual performance specifications. Also, there are only a handful of photographs -- none of it in-flight.

The XP-38 was different than most of the subsequent P-38 variants. For instance, it had a full wheel for aileron control (instead of the 3/4 wheel and yoke found on successively later variants). The use of the C-series Allison V-1710 allowed for a tight-fit tapered cowling and excellent streamlining around the engine. Necessary system appendages (scoops, vents, radiator housings, etc.) were far smaller than on subsequent variants, all attempts to minimize drag and maximize aerodynamics. The propeller spinners were 'pointier' and the propellers -- while counter-rotating like most P-38 variants -- spun the opposite directions (highpoint inward, instead of highpoint outward as found on all subsequent variants). (The French/British Lightnings, of which there were very few, did not have counter-rotating propellers).

YP-38

P-38, D and E

P-38F, G and H

The F model is considered to be the first Lightning to play a major role in World War II. With more powerful engines than its predecessors, strengthened wings, and wing pylons for external fuel tanks or bombs the F became the US's first truly long-range fighter, capable of flying 1,500 miles.

With the late F (F-15) and G models came an important feature: manuever or "combat" flaps. Actually, the manuever flap was a fixed, 8-degree pitch setting of the Fowler flaps. The added camber afforded a tighter turning radius and gave the pilot a much-needed tool for combat, for the early P-38 was not a nimble dogfighter. The late F and G also had a canopy that opened to the rear, whereas previous P-38 canopies opened to the right. The G's wings were strengthened to carry 300 gallon external drop tanks, further exenting the P-38s range to beyond 2,000 miles. While externally identical to the G, the H had upgraded powerplants, capable of 1,600 hp (each) wartime emergy power (WEP). The engines had a combat rating of 1,425 hp each, but were operationally limited to 1,240 hp due to inadequate cooling system -- a problem that spawned the next genearation of P-38s. One of every three was converted for photo reconnaissance, a role the P-38 was beginning to play with distinction.

P-38J

The J was a major upgrade to the P-38. The most distinguishable difference between the J and its predecessors, is the large "chin-like" engine nacelles. When the engines were upgraded in the H series, Lockheed soon realized that their full power output could not be attained with the limited cooling system. The deep chin allowed engineers to move the intercoolers from the wings to the nacelles, in between the existing oil cooler scoops. This provided greater scoop area and more efficient and simpler duct work. In addition, the wing space where the intercoolers once were was used for additional fuel tanks. The J-1's (three J prototypes) did not have the extra tanks, but some J-5's and some J-10's did.

Beginning with the J-15 production block, all subsequent Lightnings had the wingtip fuel tanks. The J-15 also had improved electrical systems, including a generator on each engine, and better turbochargers. Of all the J's built, the J-15 was the most numerous production block, 1,400 in all. The J-20's were essentially identical to the J-15's, and 350 were made. As mentioned above, The J-25 production block introduced two important features: power-assisted aileron control and dive recovery flaps.

Photo Lightnings

During the war, there was a saying that went something like "fighters win battles, photographs win wars." Perhaps the most significant role the P-38 Lightning played in a strategic sense was to provide high-speed, high altitude photo reconnaissance. Approximately one of every eight P-38 Lightnings built were either built as or modified to become so-called "Photo Lightnings." Designated F-4 and F-5, these Lightnings had several cameras mounted in the nose instead of guns and ammunition. Like their P-38 siblings, the F-4/F-5 aircraft evolved over time, and often no two aircraft were alike, as many field modifications were made to adapt to specific needs.

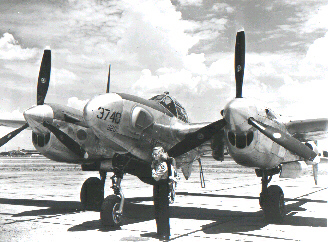

F-5E and WASP pilot

Equipped with only cameras, fuel and speed, "Photo-Joes" usually flew solo deep over enemy territory to bring back very valuable photo intelligence. While most of their missions were conducted at high altitude, some very low-level, high speed operations were conducted in the days leading up to D-Day, providing accurate information of gun and troop placements just before the Allied invasion. Many F-4/F-5s were painted in a special paint called PRU blue, in an attempt to camouflage the aircraft against the sky. The effect was only mildly successful, and eventually, just like their P-38 counterparts, F-5s were delivered in their bare metal skins.

P-38L

With the L series, Lockheed fixed most of the remaining issues with the plane and added a few new features, such that it became more or less the definitive Lightning -- the plane Kelly Johnson had envisioned several years before. It met practically all the expectations originally conceived and exceeded others not originally conceived, such as photo-reconnaissance and formation bombing.

The L was also the only series to be produced under contract by a different manufacturer than Lockheed. In anticipation of increased demand for the P-38, Consolidated-Vultee built 113 P-38L-5-VN's (VN for Vultee Nashville) before the contract for 2,000 was cancelled due to the war's end. In all, nearly 4,000 P-38L's were made, making it the most numerous variant. Many of these were converted to F-5 Photo Lightnings and 75 were converted into the two-seater P-38M Night Lightning.

There are a few differences between the P-38J-25 and the P-38L-5: The L-5 has

- different engines (but same ratings, yet some sources say that the L's engines could run WEP at 1725 HP, rather than 1600)

- landing light inset in leading edge of left wing rather than a retractable light under wing as on the J

- improved fuel system

- tail warning radar

- improved turbosuperchargers

- hard points for Christmas tree rocket launchers (standard)

Equipped with two 300 gallon drop tanks, a fully-loaded P-38L-5 could fly to targets nearly 1,000 miles away, spend 15 minutes at the target taking care of business and make the 1,000 mile return flight, provided the pilot was trained to use special fuel conservation techniques. These missions taxed every ounce of the pilot's effort, as they typically lasted 9+ hours, with most of that time high above the barren Pacific.

P-38M (a.k.a "Night Lightning")

Nearly 40 mph faster than the larger Northrop P-61 Black Widow nighttime fighter, the P-38M "Night Lightning" was to serve as a dedicated radar-equipped night fighter. The Night Lightning had a ASH-type radar scanner mounted in a streamlined housing under the nose. Flash nozzles were installed on the guns and cannon to shield the pilot's eyes. The rear compartment was very cramped and even with the bubble canopy providing more headroom than on the two-seat trainer P-38s ("piggybacks"), the P-38M radar operator had to be somewhat diminutive in size.

Lockheed modified 75 P-38L-5-LO's into this special-purpose two-seater fighter, but only a few reached the Pacific Theatre just as the war ended. Some sources suggested P-38Ms saw limited combat against enemy night intruders. Some served the occupation forces. After the war, most were scrapped but a few made it into the national racing circuit.

References

See my Books page

About this article

Initially, I wrote this piece as part of my flight simulator model documentation, to give virtual aviators some history of the plane.

There are many fine web pages out there dedicated to the P-38, and I doubt this meager effot adds much to the body of knowledge. Nevertheless, I have put this piece on my site and add to it once it a while, hoping to eventually have a comprehensive story of the P-38 as part of my site.

I suspect each of the historical photographs can be attributed to US Army Air Corps and/or Air Force.